The Tsimane

photo: M. Gurven

The Tsimane' are an Amazonian forager-horticulturalist group inhabiting a vast area of lowland forests, and savannas east of the Andes in the Beni department of Bolivia. Tsimane make a living through swidden agriculture, hunting, fishing, gathering, and occasional wage labor. Approximately 9000 Tsimane' live in about 80 small villages, typically consisting of extended family clusters (50-150 people) that vary considerably in river access, surrounding game densities and access to market goods. There also exists great variation in the extent of integration into the larger Bolivian society and economy among the Tsimane, continuously increasing with proximity to towns. While no villages have running water or electricity, up to 30 villages now house schools where students learn to read and write in both Tsimane and Spanish The Tsimane are tentatively making small steps towards acculturation but appear hesitant due to a desire to maintain a social identity and an omnipresent mistrust of Bolivian nationals.

photo: J. Winking

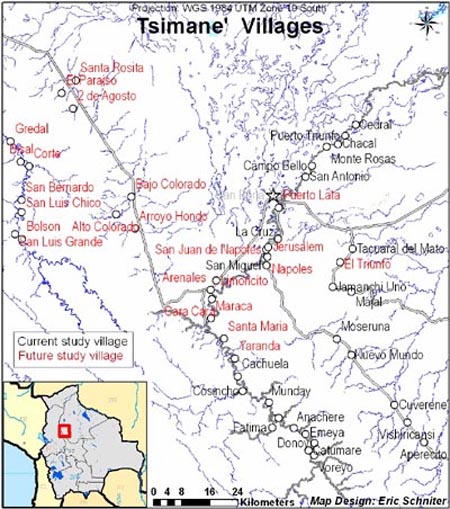

Tsimane' villages (see map below) between the departments of La Paz and Beni of Bolivia tend to be distanced from non-indigenous villages with Bolivian nationals and are located primarily along drainages, streams and rivers in the Amazon's Maniqui and Quiquibey river systems, and along seasonally impassable logging roads. Village structure is constantly in flux because Tsimane' are semi-sedentary: men and women tend to move at some point in their lives.

full image (1,175 KB); map design: E. Schniter

Although the Tsimane' were exposed to Jesuit missionaries in the late 17th century, they were never successfully settled into missions and remain relatively unacculturated to the larger Bolivian society. Tsimane' also have remained culturally and linguistically distinct from other indigenous groups nearby. Though Tsimane' have inhabited the area for hundreds of years and have been in continual contact with neighboring indigenous groups such as the Yuracare, Trinitarios, Tacanas, Reyesanos, and Moxenos, their language is an isolate, even within Bolivia. Tsimane' vocabulary and grammar are similar only to those of the Moseten, a neighboring Amerindian group who inhabit the western stretches of Tsimane'land.

photo: E. Schniter

The Tsimane' economy is based on small-scale cultivation of corn and sweet manioc (mostly consumed in the form of chicha, a fermented drink), plantains, rice, as well as fishing, hunting, and gathering wild forest products. Each adult, or husband-wife pair maintains a number of fields in various stages of cultivation. Forests house a wide variety of flora and fauna that are foraged for, while rivers offer numerous species of fish (up to 30 kilos in size!) and relatively fertile (though flood-prone) soils near their banks for cultivation. The Tsimane employ various tactics to acquire fish, including hook and line, bow and arrow, occasionally nets, if available, and also make use of handmade weirs and gathered poisons during communal barbasco events, especially during the dry season months from May to October.

photo: M. Gurven

Hunting also plays a varyingly important role, depending on the game densities surrounding each community; those near San Borja have experienced the sharpest declines. The most important species by total biomass harvested include (in descending order) collared peccary, Brazilian tapir, grey-brocket deer, howler monkey, agouti paca, white-faced capuchin monkey, and coati (Gurven et al. 2006). The Tsimane' hunt mainly with the use of rifles or shotguns, sometimes with the use of hunting dogs, and with machetes. However, the use of bow and arrow is not uncommon, especially when ammunition is not available.

photo: A. Gillespie

Households (which consist of one to four nuclear families) are also the units of food distribution, although it is not uncommon for portions of fish and game to be distributed to other nearby unrelated households. While the distribution of raw foods is limited relative to that encountered among many foragers, requests of cooked foodstuffs are not uncommon, and are rarely denied.

High levels of visiting and sharing among members of different households are usually associated with beer consumption. Huge vats of fermented manioc, corn, or plantains always attract visitors from other household clusters and even other villages, who gather around to drink and talk about hunting, fishing and other activities. Experiences, tales, myths, stories, songs and other cultural codes are also shared at these times, both seriously and through jokes. Prior to formal education and written culture, the system of traditional education among the Tsimane' was handled by the oral and musical traditions that are still alive and well today and largely in the domain of older adult expertise.

photo: E. Schniter

The nuclear family unit of parents, aunts and uncles, children of these adults, and grandparents is the core of Tsimane' life. Marriage among the Tsimane' is not marked by formal celebrations, symbols, or rituals, though it is a socially recognized convention and social structure. A couple is considered married if they sleep together under the same roof in a socially recognized way for more than just a brief period of time. The median age of first marriage is 21 for males and 16.5 for females (Winking, 2005). Marriage among the Tsimane' is fairly stable, however, with less than 20% of the unions ending in permanent separation and most cases of "divorce" occurring during the first years (Winking et al., 2007). With the exception of a few places where missionaries have influence, polygyny is widely accepted. Though it is not very common (and less so with younger generations), there are cases of polygynous marriages (usually involving 2 wives) in several villages (6% of men in the population according to Winking, 2005), most of which are sororal.

photo: M. Gurven

Infants and babies are primarily cared for by their mothers, but also by older siblings and fathers. Samples of time allocations made in villages by Winking (Winking et al., 2009) reveal that men contributed 8.6% of their time in the village to parental care (mostly in the form of play), as opposed to women who contributed 39.4% of their time to parental care (with 17% of this mothering time accounted for by breastfeeding, and much of the remaining time in the form of grooming). Tsimane' woman, on average, become mothers by age 18, grandmothers by age 36, and greatgrandmothersby age 54 (Gurven and Kaplan, 2007). Within marriages, inter-birth intervals average approximately two and a half years. Approximately four-fifths of children born live to the age of 15. The relatively high fertility of Tsimane' (Total Fertility Rate is 9 children) gives older individuals greater opportunity to help descendant kin.

photo: E. Schniter

Older adults are collectively referred to as isho' muntyi (old people). Getting old, among the Tsimane', is most consistently perceived as a function of physical decline past the peak ages of physical strength (roughly the 30's). Physical declines directly impact the forms of subsistence that are strength-dependent (Gurven, Kaplan, & Gutierrez 2006; Gurven & Kaplan, 2006 provides detailed information of time allocation to various forms of investment as predicted by age- summarized below). As a result, older men shift activities away from hunting and rely more heavily on farming, with time devoted to farming peaking among men in their fifties. Older women, however, spend much of their productive time processing, rather than directly acquiring food. By their sixties, women are directing much more of their production to grandchildren than to children, and no longer have any sub-adult children to invest in. Men provide comparable amounts to children and grandchildren in their sixties. Tsimane' men and women in their seventies do not contribute many calories to their descendents, though they are still often capable of making non-caloric contributions.

Tsimane' older adults are respected and valued for their important contributions. Village elders, when referenced publicly, are sometimes given honorary titles of jayej (grandmother) or via' (grandfather) even by non- relatives, and deferred to for their superior knowledge of traditional stories and myths, ethics for living in accordance with (and not angering) the spirit-world, animal and plant knowledge, locations of hunting grounds and sacred locations, as well as for their superior knowledge of family lineage histories and past events. Older adults -- by making their opinions and intentions clear at home -- also tend to exert their influence on younger chiefs and junior individuals who are more vocal in public. Opinions and wishes of older adults are acknowledged and heeded because it is widely believed that unlike younger adults, they "know how to think [about work and what needs to be done]" (chij dyiji'jiyequi). Furthermore, because of their unique ability to "think", they are especially skilled in planning out tasks and consistently executing them with efficiency and accuracy, contributing to their roles as instructors, exemplars, and encouragers of skill development in younger kin.

photo: A. Gillespie

Today's Tsimane population is divided between areas that have been formally protected as indigenous territories and those that have been opened to logging interests (Ellis and Gonzalo 1998). The Tsimane territory proper (Territorio Indigena Chimane) extends from approximately 50 km north of San Borja to 100 km south of the town along the Maniqui River, encompassing over 300,000 hectares (CIDDEBENI 2001). Parcels of comparable size have been protected to the east and west of the formal Tsimane territory (Territorio Indigena Pilon Lajas and Territorio Indigena Multietnico), that also hold numerous Tsimane settlements as well as those of neighboring indigenous groups.

A number of Tsimane settlements are located within areas that have been ceded to logging interests. The Tsimane have long had a tumultuous relationship with logging groups. At first glance, the relationship may appear to be one of mere exploitation, but in actuality, it is quite complex and often characterized by mutual dependence and mutual distrust. While most Tsimane hold negative opinions of the loggers and their presence, the industry remains one of the only constant sources of income for the Tsimane, and there is no stigma associated with working for them.

photo: J. Winking

For the majority of Tsimane, access to modern health care and social services is extremely limited, though the Tsimane Health and Life History Project has been continually improving access to health care since 2002. Health care expenses are covered by the Bolivian government for pregnant women and infants, but the journey to the San Borja hospital often requires many days of travel and is impractical for most. Recently, immunization teams have begun traversing the rivers in an attempt to vaccinate all children against the most common tropical infectious diseases. These efforts appear to be having an appreciable impact, as Tsimane mortality rates for infants and the elderly have dropped in the last decade. The infant mortality rate remains nearly one and a half times that of the greater Bolivian population, however, and nearly 12 times higher than for the United States (CIA 2004).

Like many indigenous populations, the Tsimane find themselves caught between two worlds, both offering unique facets of security, comforts and hopes. Although the Tsimane have maintained their cultural identity and succeeded in preventing the total outright usurpation of their native territory, the direction of the recent trend has clearly been towards greater acculturation, something the Tsimane greet with great ambivalence. The first cultural elements to be adopted by indigenous populations are most often the most technologically pragmatic-machetes, shotguns, metal pots. Many of the Tsimane, however, particularly the younger men, have begun adopting Western articles that have no practical utility, only the ability to display status. These items include radios, bright shoes and clothing, watches whose owners may or may not be able to read them, glasses of random prescription, and many others. The fact that the Tsimane youth are looking to Bolivian nationals and Western culture to define status may point to changing attitudes and values, perhaps brought on by ever improving and available technology, or more frequent and immersive contact with the colonizing population. Fortunately for the Tsimane, they have had a long enough history of interaction and cultural resistance to have already established robust political and economic infrastructures to ensure the continuation of their culture, their social identity, and their way of life for some time to come.

The Tsimane' offer some of the last remaining opportunities to study the effects of kin, culture, and ecology on aging in a small-scale, natural fertility, kin-based, subsistence society, and for this reason have been the focus of study by the UNM-UCSB Tsimane' Health and Life History Project

photo: M. Gurven

Above text adapted from the following sources:

Gurven, M. 2004. Economic Games Among the Amazonian Tsimane: Exploring the Roles of Market Access, Costs of Giving, and Cooperation on Pro-Social Game Behavior. Experimental Economics, 7:5-24.

Schniter, E. 2009. Why Old Age?Non-material Contributions and Patterns of Aging Among Older Adult Tsimane. Doctoral Dissertation: UCSB.

Winking, J. 2005. Fathering among the Tsimane of Bolivia: A Test of the Proposed Goals of Paternal Care. Doctoral Dissertation: UNM.